When family violence is used by someone against their intimate partner, it can be called intimate partner violence (IPV). IPV is nearly always a pattern of coercive and controlling behaviours, sometimes called coercive control.

Coercion is the use of force or threats to intimidate or hurt someone and make them afraid. When someone is afraid of or intimated by their partner, they’re more likely to do what their partner wants them to do. This can lead to many parts of their life being controlled by that person, such as; who they keep in touch with, what they do, what they wear, what they eat.

They’re also likely to stop doing things they’re partner doesn’t want them to do, and have their freedom to live the way they want limited or taken away altogether. They may give up working, studying, shopping, keeping in touch with family and friends, doing sports or hobbies they enjoy, volunteering, watching movies or reading books they like, going out of the house, etc. The list is endless.

A person trying to coerce or control their partner or ex-partner will target what is most important to that person to most effectively control them and keep them trapped. Controlling behaviours are used to isolate a person and make or keep them dependent on the abusive partner. Even if someone manages to separate from the person controlling them, that person will often continue to coercively control and abuse their ex-partner.

Often the pattern of coercive controlling behaviours is quite subtle to start with and become more obviously controlling over time. Someone may become isolated as they try to please their partner by, for example, avoiding contact with friends or family the partner doesn’t like or because their coercive controlling partner never leaves their side. Often the fear grows because of intimidation or violence or threats or constant monitoring and surveillance, and the isolation gets worse.

Coercive control is an attack on a person’s dignity.

Coercive controlling behaviours have a cumulative impact. That means that on any one occasion, the person is responding to their partner’s abuse at that moment as well as all the ways their partner has harmed them, and others, in the past.

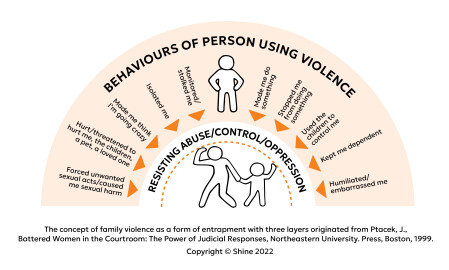

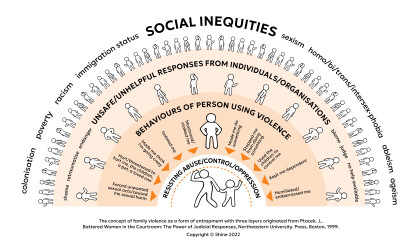

The layers of entrapment

People are entrapped (or trapped) not only by a partner (or someone else close to them) who uses coercive controlling behaviour. They are often also harmed and entrapped by unsafe and unhelpful responses of others that ignore or minimise the abuse, blame the person experiencing abuse or put them in greater danger.

People who experience family violence often seek help, but the person abusing them will often actively try and stop them from getting the support they need. This can include manipulating others, creating fear or using control to block their attempts to get help.

Experiencing social inequity (colonisation, sexism, poverty, racism, heteronormativity or homo/bi/trans/intersex-phobia, ableism, ageism) limits people’s safety options and increases the impact of the abusive person’s coercive controlling behaviours.

Watch this space for further blogs to come that relate to various forms of social inequity and this third layer of entrapment:

- Gender, patriarchy and family violence

- Colonisation and family violence

- Rainbow and Takatāpui relationships

- Disabled and elderly people

Note: We use the term ‘family violence’ which is defined under the Family Violence Act 2018. This Act replace the Domestic Violence Act 1995, and ‘domestic violence’ means the same thing. ‘Family harm’ is a term used by NZ Police that does not have a legal basis.